Don't buy The Dip

( My reviews are aimed at helping you decide whether you should read something, rather than assuming your meaning of “good” or “bad” is anything like mine. )

The Internet, and more traditional bookshelves, are full of advice on when to start something, how to start something, and how to beat procrastination or self-limiting beliefs or imposter syndrome or whatever the author thinks is stopping you from reaching your full potential. But there’s much less content on when you should quit, on why you should consider not spending time on a project at the expense of other projects, and how to sensibly work through those decisions. With that opportunity cost being one of the few concepts I’ve kept from my O’level economics, I was particularly interested in Seth Godin’s The Dip - with its subtitle of “The extraordinary benefits of knowing when to quit ( and when to stick ).”

Picture by Joi Ito - Seth Godin, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10763024

To explain what the book is about, and why I was so excited by it, I’d like to quote extensively from the introduction:

Most of the time, we deal with the obstacles by persevering. Sometimes we get discouraged and turn to inspirational writing, like stuff from Vince Lombardi: “Quitters never win and winners never quit.” Bad advice. Winners quit all the time. They just quit the right stuff at the right time.

I love this. I think there are many “Gossamer Aphorisms” like this that are shared and followed because they’re snappy phrases, rather than because they genuinely reflect some kind of universal truth. So I am already onboard.

Most people quit. They just don’t quit successfully. In fact, many professions and many marketplaces profit from quitters – society assumes you’re going to quit. In fact, businesses and organizations count on it.

If you learn about the systems that have been put in place that encourage quitting, you’ll be more likely to beat them. And once you understand the common sinkhole that trips up so many people (I call it the Dip), you’ll be one step closer to getting through it.

I’m assuming this part alludes to the way some companies or industries operate, from introductory offers that silently expire, to subscriptions that make it so hard to cancel. I’m into understanding the adversarial relationships that can develop between customers and businesses, so I really like the way this is being set up.

Extraordinary benefits accrue to the tiny minority of people who are able to push just a tiny bit longer than most.

Extraordinary benefits also accrue to the tiny majority with the guts to quit early and refocus their efforts on something new.

And this ends on context-dependent advice, rather than an over-simplistic rule for all situations. This sounds great, I’m ready to be inspired. The point is well made, that there’s the assumption that all it takes to succeed at something is perseverance, to keep trying and trying until you succeed. This is a valid strategy in very limited situations - for example sports matches where there is no option but to play until the end. But in life in general we usually have many more options than there are within that limited problem space.

Thinking about the effective application of limited resources I’m specifically reminded of my time with a former employer, who would take a “you have to be in it to win it” attitude to sales, devoting sparse resources to any opportunity that arose, resulting in over-stretched staff and minimum effort for every potential sale. At some point the company adopted a much smarter approach of ranking opportunities, methodically judging which were most likely to pay off, and became much more successful as a result of assigning resources more intelligently. This was a real mindset change, and it took significant fortitude to ignore the natural tendency to loss aversion, to not wanting to give up any possibility.

It’s especially pleasing to hear this attitude from someone as successful and well known as Seth Godin. Godin is a best-selling author, multi-millionaire, and is well regarded in marketing circles and among business leaders. From someone with this kind of reputation we usually hear enthusiastic advocacy for perseverance, from those who’ve succeeded by persevering, it’s rare to have someone gaining attention and success from explaining how good they are at giving up on projects or ideas. A situation akin to only asking lottery winners whether you should play the lottery or not.

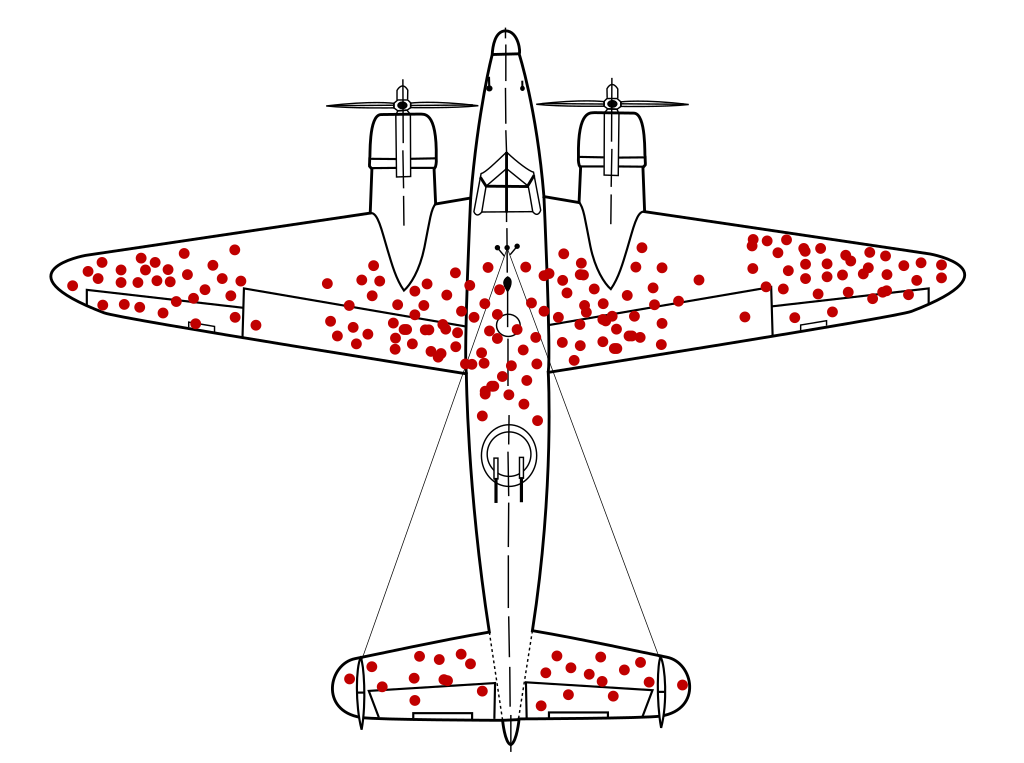

( while a good book, if I remember correctly Angela Duckworth’s Grit suffers from this - and if you’re not familiar with the idea of “Survivorship Bias” and the related story of the World War Two bomber armour do check out the Wikipedia page on this, and the inevitable picture of a plane seeming to have a rash )

All pieces mentioning Survivorship Bias must include the "measles plane".

So having established this point the book raises obvious questions: how to decide when to stick to something? And how to decide when to quit?

I’m surrounded by half-completed ideas, exciting new projects, exciting old projects, potential collaborations, or promising task lists, and more. A tried and testing framework of how to prioritise, or selectively abandoned, these ideas is just what I need. So I looked forward to what examples Godin would give, and what methodologies he’d suggest. Here… we… go…

But instead it seems that “you should quit things that won’t pay off” is the limit of the book’s thinking. Instead, there’s some shaky examples and worse reasoning, seemingly to pad out a book that checks in at maybe 80 pages of well spaced and large print. Take for example the phenomenon of Zipf’s Law, potentially an insight into human nature, but it appears to be cited incorrectly1 in a sentence, and then we move on. Similarly Godin claims that the USA was only in the Vietnam War for so long due to Nixon’s pride, which is an incredible oversimplification. Arguments are made against aiming to be well rounded, arguing that only specialists are rewarded - but this goes against modern thinking ( I think we’re finally seeing the value of generalists, as shown by responses to David Epstein’s Range - which I describe here ) and is only justified through very limited examples referring to specialist professions.

Another analogy that only works if you don’t think about it is this one…

From a test-taking book: “Skim through the questions and answer the easiest ones first, skipping ones you don’t know immediately.” Bad advice. Superstars can’t skip the ones they don’t know. In fact, the people who are the best in the world specialize at getting really good at the questions they don’t know. The people who skip the hard questions are in the majority, but they are not in demand.

This is a terrible analogy. Optimising performance in the time-boxed and tiny “problem space” of a written exam is entirely different to the more general context of success in an entire field - not withstanding that the definitions and boundaries of that field can be defined by tradition, and history, and therefore will be relatively arbitrary.

Similarly later on, Godin says “And yet the real success goes to those who obsess.” This contains the massive assumption that you are obsessing on the right thing, an issue which Godin fails to address. In a later blog he states it’s important to ask the question of whether you’re facing “a dip or dead end” rather than know how to find the answer, which is what someone who doesn’t know the answer would say.

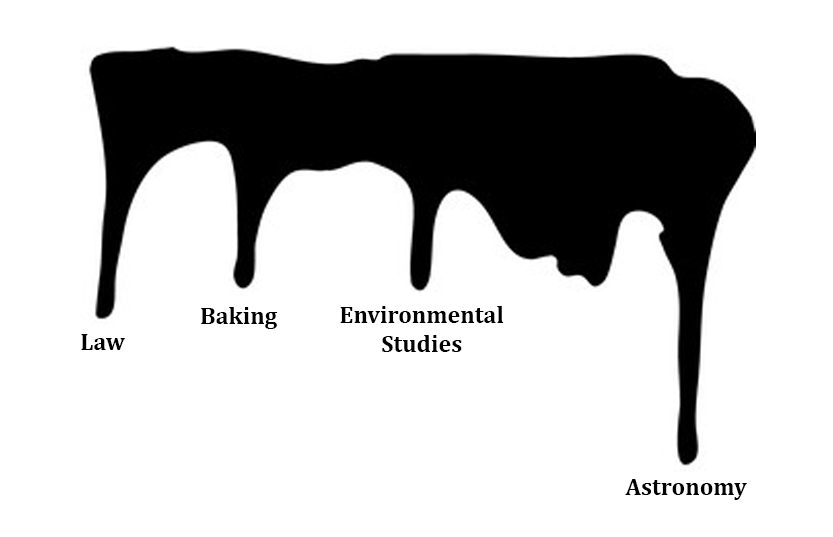

For me, a much better way of thinking on this is Taylor Pearson’s “paint drop method”. Which also works as a counter to that awful “do what you love and you’ll never do a day of work in your life” rubbish.

From Pearson's blog, you should read it.

As a side thought, this single-minded approach also leads to professions dominated by group think, where new ideas are impossible, and concepts or lessons aren’t learnt from similar but different disciplines. For me personally this alludes to the cyber security industry’s poor understanding of conflict - something it could gain from the military or sports; or the wargaming discipline’s poor understanding of development or marketing - concepts it could learn from software development or marketeers. If you’re the kind of person who’s read this far into this kind of review, I suspect you have your own to hand too.

Overall I love the idea of the book but it is just one big “reckon”2, there’s no research ( in vast contrast to Duckworth’s Grit mentioned above ) and there are barely any anecdotes. Some examples cited when the book was written in 2007 haven’t aged well, for example noting how Biden should have persevered in a Presidential race in 1988 but that chance is now forever lost… of course that being two term Vice President and current POTUS Biden at the time of writing.

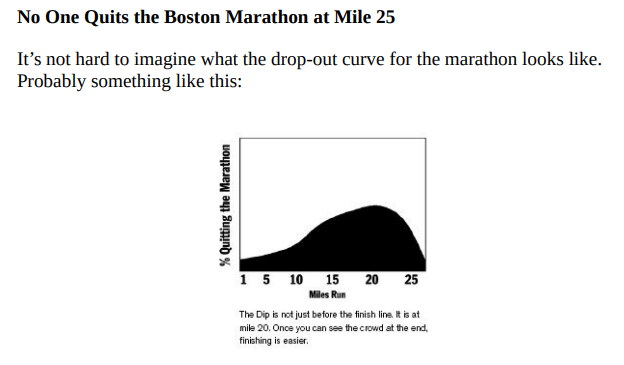

Another example is this commentary on imagined statistics:

I would argue that your imagination is not a viable source of data.

Godin assumes what the dropout rate is for the Boston marathon, then comments on it. This is a real event, presumably with real data out there somewhere. Something on this would be fascinating, especially the variations for different marathons based on weather and culture and more. I can’t help thinking if this was touched on by Freakanomics it would have its own chapter, but for Godin he just makes up the numbers.

The standard I expected of the entire book is really only present in a few pages under “Three Questions to Ask Before Quitting”. This starts to get into much better points on how to decide in advance what your quitting point is on a project, to determine whether you’re panicking, why you aren’t succeeding, and what measurable progress you’re making. This links nicely to earlier points Godin makes, on whether you’re in a “dip” and so will rise again with perseverance, a “cliff” so best to stop before you fall off, or a “Cul-de-Sac” - where things won’t get worse, but they won’t get better. However even here there’s no criteria listed, or personal experience shared, on how to predict which of those three states you’re facing.

If you need an impetus to do something, or start asking questions about where you are in a particular context, this book may be useful, just not in the way it’s intended to be. According to Wikipedia “The Dip peaked at #5 on the New York Times Best Seller List and sold 100,000 copies in its first month of release.” So there’s something there… but not for me. There’s no solid advice, no methods to try, not even any inspirational anecdotes to emulate. Godin’s point that no-one advocates for quitting is well made, as are the benefits of being one of the few who made it through a dip, but there’s so much more thought needed here, and it’s all alluded to, but never explored. There’s a great paragraph within The Dip that sums up what this book does and doesn’t say:

Persistent people are able to visualize the idea of light at the end of the tunnel when others can’t see it. At the same time, the smartest people are realistic about not imagining light when there isn’t any.

How to figure out if you’re persistent, or smart, or whether you should be persistent, or you should be smart, or how to know whether your seeing light that isn’t there or light no-one else can see? You’ll be no wiser after finishing this book than you were when you started.

Epilogue

I would like to thank Felicity Brand, Jude Klinger, Russell Smith, Alice Sholto-Douglas, and Denny Dien from Foster for all their help and comments.

The Dip is a very short read, but this video is a good summary, and even shorter.

-

Zipf’s Law relates to the distribution and usage of words in languages, and how the distribution of popularity within human-driven systems might reveal something about the choices people make in relation to effort versus availability. There’s a really intriguing and difficult subject here, but instead we get “Winners win big because the marketplace loves a winner” as a one line explanation and the book moves on. ↩︎

-

By “reckon” I mean “a very confident opinion based on no observable facts or acquired knowledge, put with the confidence of someone who has carried out years of research”. It is best encapsulated in this 90 second comedy sketch by Mitchell and Webb. And yes, I still need to get “sidenotes” or some other mechanism in place to make it easy to share these kind of thoughts without breaking the flow. But now you know what a “reckon” is, you’ll be spotting them all over the place. ↩︎